The Old Testament contains a variety of laws and legal categories. Some laws govern civil matters, other laws (e.g. Deut. 22:8), to laws governing the clothes individuals wear (e.g. Num. 15:38). Pragmatically, Christians do not follow all these over 600 commandments. So, can the Old Testament law be used at all in developing Christian ethics? How much should be used? Do Christians just arbitrarily pick and choose laws to follow?

Because the prescribed law has changed, the Old Testament law is only useful to form a Christian ethic when using a contextual-grammatical analysis to discover the authorially-intended theological principle within the law. Jesus interprets “weightier matters” in the Old Testament law as being, “justice, mercy, and faithfulness” (Matt. 23:23). In that sense, it is the principle behind the prescribed laws that are weightier than certain prescriptions themselves. The thesis will be expounded by defining the nature of the law, understanding the purpose of the law, and practically applying this hermeneutical principle.

Nature of the Law

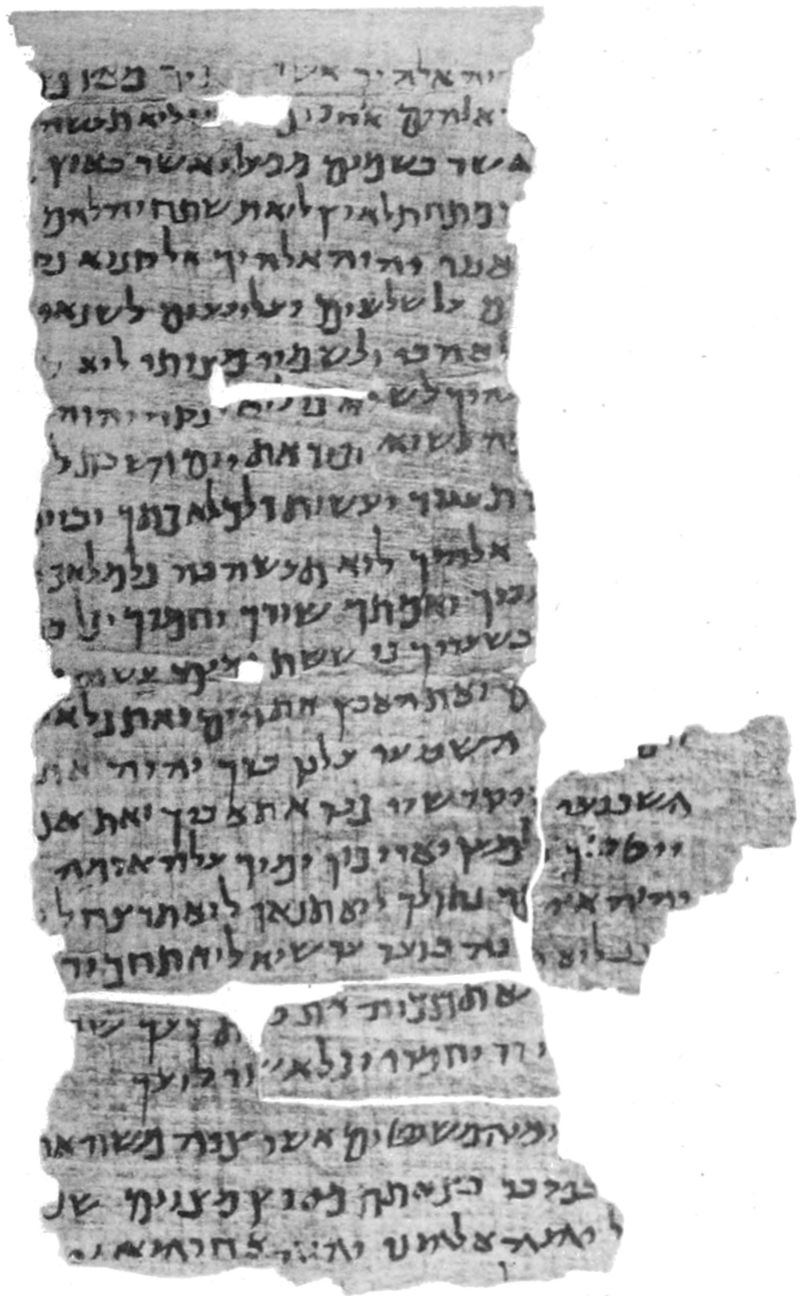

As far as the nature of the Old Testament law is concerned, it is the very things God revealed to Moses in order to set up a theocracy for the descendants of Jacob. To be more specific, the Mosaic law is given in the context of a suzerain-vassal covenant. This covenant guaranteed the Israelites, “certain benefits including protection. In return, the vassal [Israelites] was obligated to keep specific stipulations certifying loyalty to the suzerain alone.”[1]

Alongside the historic significance of the law, the ontological nature of the law is important as well: what makes the law good and right? Socrates brings out a classical problem to divinely derived law: “Does God command X because it is right, or is X right because He commands it?”[2] The problem here is twofold. If a law is right simply because God commands it, then it would bring out the possibility that God could change is mind regarding what is right. On the other hand, if a law is right therefore God commands it would mean God is subject to this law which ultimately is more powerful and thus should be God.

The supposed dilemma, while it could do significant damage to a polytheistic system (whence Socrates wrote) becomes only a bifurcation in the Christian theistic tradition because it discounts theology proper. Within Christianity, the law is good and right because it flows from God’s nature. David Jones calls this understanding “authority is law.”[3] Jones uses four things to defend this understanding of the law: sanctification, the equivalence of sin to breaking God’s law, the fate of the unevangelized, and necessity and sufficiency of the atonement. Thus, identifying ethical duty is an extension of identifying God.

The Purpose of the Law

Understanding the purpose of the Mosaic law is key to its application. Paul sees the purpose of the law as being a guardian, “So then, the law was our guardian until Christ came, in order that we might be justified by faith” (Gal. 3:24). Thus, for Christ, the purpose of the law is entirely Christological: to reveal mankind’s sin and need of a savior.[4] This still brings the question: what of the law should individuals follow today? Hebrews 7:12 answers, “For when there is a change in the priesthood, there is necessarily a change in the law as well.” According to Mosaic law, Jesus’s priesthood is illicit due to his lineage from the tribe of Judah. The author of Hebrews acknowledges a change in priesthood from the Levitical taxis to the Melchizedek taxis. Astoundingly, the author of Hebrews announces the law has changed. But what type of law?

Classically, the law was divided into three parts: civil, ceremonial, and moral. So perhaps the civil and ceremonial portions have changed; but the moral laws have remained. The issue with this is that no biblical author utilized the tripartite notion of the law. It would be anachronistic to presume that it what the author of Hebrews is talking about. Furthermore, the word “change” in relation to a whole idea “law” could not mean change in only part. Paul Ellingworth comments on the word law, “Here the author indicates a change, not merely in particular laws, but of the entire legal system. . .The change of law introduces, not a state of lawlessness, but an order which imposes stricter obligations.”[5] Why did God instate a law that he knew would be changed? Moises Silva answers this concisely, “Not because there was anything intrinsically wrong with [the law], but in divine arrangement it was designed as a shadow, anticipating the substance. The substance, therefore, far from opposing the shadow is its fulfillment—this is perfection.”[6]

Practical Application

The law has changed for the person under the New Covenant; however, this does not render Old Testament law useless. Principles reflecting God’s character and nature still serve as the foundation of the law and make it useful for believers under the New Covenant. Jones presents three positions on the law’s relevancy as discontinuity (only NT is relevant), continuity (OT law is binding), and semicontinuity (moral continues, civil and ceremonial passes away). Principalization is another position that could be included under the semicontinuity category, but does not rely on the tripartite division. No matter the category of law, theological truths exist in the undercurrent of law that are still applicable.

Consider for instance, in the prohibitive laws against adultery (Deut. 22:23-27), the death penalty is given. However, there is an exception in the case of a relationship in an open field where although the, “young woman cried out for help there was no one to rescue her” (v. 27). The presumption of innocence is an undercurrent in this case law. The text itself, though pertaining to civility in theocratic Israel, still has an undercurrent of a moral principle that can be applicable on the individual level. If one believes (with a degree of uncertainty) he may have been wronged, he should presume innocence on the suspected party until due process has taken place. Presuming guilt requires an omniscience that no mere human possesses.

Conclusion

The Old Testament law is useful for Christian ethics on a principle level. This makes the Old Testament law relevant and not binding in line with the Jerusalem Council in Acts 15. Also, it avoids the tripartite divide and apply methodology which can see some portions of Old Testament law as irrelevant if defined as civil or ceremonial. The deeper theological principle underpinning all of the Old Testament law is extremely relevant and applicable when mined considering the historical and literary contexts, as well as the authorial intent (divine and human).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bonhoeffer, Dietrich. Ethics. touchstone ed. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995.

Cowan, Steven B. The Love of Wisdom: A Christian Introduction to Philosophy Steven B. Cowan, James S. Spiegel. Nashville, Tenn.: B&H Academic, 2009.

Ellingworth, Paul. The Epistle to the Hebrews: A Commentary On the Greek Text. The New International Greek Testament Commentary. Grand Rapids, Mich.: W.B. Eerdmans, 1993.

Hill, Andrew E., and John H. Walton. A Survey of the Old Testament. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan, 2018.

Jones, David W., and Daniel R. Heimbach. An Introduction to Biblical Ethics. B and H Studies in Biblical Ethics. Nashville, Tennessee: B&H Academic, 2013.

Lane, William L. Word Biblical Commentary. Edited by David A. Hubbard, Glenn W. Barker, and John D. W. Watts. Vol. 47, Hebrews 1-8. Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson, 1991

[1] Andrew E. Hill and John H. Walton, A Survey of the Old Testament (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan, 2018), 63.

[2] Steven B. Cowan, The Love of Wisdom: A Christian Introduction to Philosophy Steven B. Cowan, James S. Spiegel (Nashville, Tenn.: B&H Academic, 2009), 364.

[3] David W. Jones and Daniel R. Heimbach, An Introduction to Biblical Ethics, B and H Studies in Biblical Ethics (Nashville, Tennessee: B&H Academic, 2013), 47ff.

[4] Cradle cross crown 500

[5] Paul Ellingworth, The Epistle to the Hebrews: A Commentary On the Greek Text, The New International Greek Testament Commentary (Grand Rapids, Mich.: W.B. Eerdmans, 1993), 374.

[6] Cited from William L. Lane., Word Biblical Commentary, ed. David A. Hubbard, Glenn W. Barker, and John D. W. Watts, vol. 47a, Hebrews 1-8 (Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson, 1991), 181.